Anastasia Talbot

BORN: Owning, Kilkenny, Ireland, 1854.1

DIED: Porirua, 5 December 1930.2

Biography:

Anastasia was born in Owning in County Kilkenny in 1854, the youngest of six children.

Her family seem to have been reasonably prosperous farmers and the Talbot family remain farmers in Owning to this day. There also seems to have been a tradition of learning in the family. One of Anastasia's cousins was Thomas Talbot (1818-1901), a prominent intellectual, teacher, poet and politician in Newfoundland, Canada in the late 1800s3.

We know nothing of Anastasia's early life, although we can make some guesses about the sort of life the youngest daughter of a Kilkenny farmer might lead. This would have been a life primarily centered on the family and the farm, the local school, the church and the rural community around Owning.

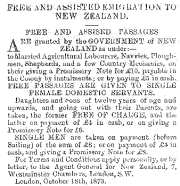

Nor do we know what prompted her to emigrate by herself to the other side of the world. However, in the 1870s, the New Zealand Government embarked on a massive programme of economic expansion based on borrowing £10 million over 10 years to finance infrastructure development and to assist immigration. Agents were active in Great Britain and Ireland, advertising and recruiting suitable candidates for immigration to New Zealand. Successful candidates were offered assistance with paying for their passage to New Zealand, but single female domestic servants, which is the category Anastasia applied under, were offered free passages. Almost all the immigrants were from England, Scotland or Ireland with the Irish comprised about a fifth of the total. These were typically Catholic families joining their kin already in New Zealand, but also included was a large proportion of single people, especially single women, no doubt attracted by the promise of free passage4. Clearly, Anastasia knew about this programme of assisted immigration, but we can only guess at what might have prompted the decision to take advantage of it. We do know that one of her older sisters (probably Ellen) emigrated to Australia5. Maybe Anastasia planned to join her sister after making her way to New Zealand.

In 1875, when she was only 21, Anastasia said goodbye to her family for the last time and made her way from Owning to Plymouth in England. There she embarked on the ship Caroline with 318 other immigrants, all bound for a new life in New Zealand.

The Caroline was a fine, powerful, full-rigged ship of 984 tons, 260 feet in length. She was capable of daily runs of over 300 miles per day and on this voyage took 93 days from Plymouth to Nelson, leaving Plymouth on 12th October, 1875 and arriving in Nelson on 14th January, 1876. On the whole, the voyage was an uneventful one. There was no serious sickness among the adults, although there were five deaths of infants, all months old, principally from diarrohea. There were no other passengers from Kilkenny although there were a number from other parts of Ireland. The full passenger list is interesting for its descriptions of the people on board. Anastasia is listed as one of the single women bound for Marlborough. This suggests that she had made a decision, prior to embarking, to go to Marlborough. Why she chose this destination we have no idea. On the voyage she became good friends with John and Jane Berriman and their seven children. The Berrimans were from Cornwall and also bound for Marlborough.

A fuller account of the voyage of the Caroline is given here.

After landing in Nelson, Anastasia moved to Blenheim. She was probably engaged as a servant soon after her arrival, since servants were in short supply and in demand. Employers living in Blenheim who wanted to engage a servant were obliged to travel to Nelson since that's where the immigrant ships docked. It's possible that she was first employed by a Mr. Stace, a sheep farmer with land to the south of Blenheim, in the Awatere river valley, and brought back to Blenheim by him. Another possiblity is that she acompanied the Berriman family to Blenheim.

However she got to Blenheim, we know she was employed in the Stace household by November 1876 because the 29th November edition of the Marlborough Express reported a court case in which Anastasia was witness in an action taken by Edward Jaques against H. J. Stace for assault6. Edward Jaques was also employed by Stace. The dispute between Jaques and Stace arose out of complaints, voiced by both Anastasia and Jaques, about the poor treatment given to them by their employer:

"They also condemned a rhubarb pie which was given to them for dinner. Mrs. Stace happened to overhear the conversation and told defendant [Stace], who knocked plaintiff [Jaques] down and kicked him on the head."

A dispute like this over poor treatment was most unusual. Since labourers and servants were in demand employers took care to treat them well least they move on. Letters back to England invariably praised the generous and respectful treatment new immigrants received from their employers.

Soon after her appearance in court, Anastasia entered into a relationship with a Philip Fissenden. Fissenden had arrived in Nelson with his younger brother James on the Hannibal in June 1875.7 When he met Anastasia he was employed as a labourer at a sheep station near where she was living. She became pregnant and a daughter was born on 2nd November, 1877 and christened Mary Jane.8 Unfortunately, Fissenden left his job and disappeared soon after Mary's birth. Anastasia took him to court in an effort to force him to provide support for her and the baby. The case was reported in the 5th December 1877 edition of the Marlborough Express. Anastasia is quoted:

"I charge...Philip Fisgenden [sic] with being the father of the child now in my arms. I have applied to him to contribute towards our support, but he has not done anything for us...Since taking proceedings I have seen [Philip] twice; he offered me £10, £15, and £20, but no further amount. I did not consider the amount sufficient. [He] seduced me under promise of marriage, but he has declined to fulfil that promise."9

Philip Fissenden was ordered to pay 5s a week towards the support of the child, and court costs, although the magistrate acknowledged that Anastasia might not get the money, since Fissenden had probably left the district. Eventually he did return however, and the issue of support was resolved by Anastasia agreeing to accept a lump sum of £25 in lieu of 5s a week.10

Then on Tuesday, 23rd July 1878, Anastasia married Albert Potter at the Catholic Station in Blenheim. They were married by Father Pezant, a well-known Marist priest and missionary. The witnesses to the marriage were John and Jane Berriman, her friends aboard Caroline, now living in Blenheim. Albert was registered as a farm labourer and bachelor, aged 31, although his true age was only 21. Anastasia was rather coyly described as "Daughter of Family" and a spinster, aged 24.11 Also at the wedding was Albert's mother and father and his five sisters.12

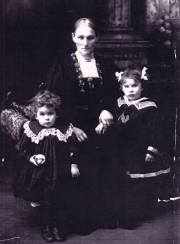

Their first child was born in 1879 and named Albert.13 The photograph on the right shows Anastasia with young Albert and Mary, outside their house in Blenheim about 1880.

Some time soon after, their relationship took a turn for the worse and Anastasia left her husband. In August 1880, Albert put a notice in the Marlborough Express:

NOTICE-This is to give notice

that I Will Not be Answerable

for any Debts Contracted by my Wife,

ANASTASIA POTTER, after this date, she

having left home without my con-

sent. -ALBERT POTTER. Aug 21. 188014

They resumed their relationship and their second son, John was born in 1881, followed by James in 1883. Their first daughter was born in 1885 and named Anastasia after her mother, but died after only eight days. Then Catherine was born in Masterton in 1886.15

We don't know what prompted the move to Masterton. New Zealand experienced an economic depression in the 1880s and 1890s and the family may have moved in search of work. Family tradition16 relates that Albert was employed by William Summers (head gardener at Glenburn sheep station in the Wairarapa) as a gardener. The two men may have known each other in England and William may have recruited Albert. However, at the time of writing, there is no supporting evidence for this story. It is more probable that Albert was merely one of many unemployed labourers moving around the Wairarapa at this time looking for any work they could find, and happened to find work at Glenburn station.

Their last child Thomas was born in 1890, as the relationship between Anastasia and Albert deteriorated further. By July 1892, it seems as though Albert had abandoned the family, and Anastasia was dependent on the charity of the North Wairarapa Benevolent Society. The Society wrote to the Wairarapa North County Council, Albert's employer, requesting that wages be given to the family rather than to Albert. In considering the matter, one of the councillors thought that "if the man did not provide for his family he should be dismissed from the services of the Council"17. This may in fact have happened, because in December, Anastasia and six children were still dependant on charitable aid. The police took Albert (named Alfred in the newspaper report) to Court, in an effort to compel him to provide maintenance for his family. In court Anastasia told of the hardship the family was suffering and said she needed £1 a week from her husband. However, because Albert was earning only £1 a week the magistrate ordered Albert to pay 12s 6d a week18.

At £1 a week, Albert was earning an extremely low wage which suggests he was one of the many victims of the economic depression, only partially employed or employed in very low-paid work. By 1896, his income had not improved and in March 1896, he was in Court again after failing to pay the 12s 6d a week to his family. The Magistrate ordered Albert to pay an additional 10s a week to clear arrears of £5 19s, and threatened Albert with imprisonment if he failed to do so.19. A month later when they returned to court Albert was able to pay £3 which went some way towards clearing the amount he owed. Albert was ordered to continue his payments, or face imprisonment.20

By August, however, the situation had worsened and they appeared in court yet again. This appearance, more fully reported than previously, shows how far their relationship had deteriorated, as well as showing the diificulties faced by Anastasia in bringing up the six children on her own. Anastasia (named Mary Potter by the court reporter) complained that Albert had failed to comply with the earlier court orders and was now £7 17s in arrears, although he had paid her £2 that very morning.

Albert then presented his side of the story, pleading he had not always beeen regularly employed and he was doing the best he could. At the moment however, he was in regular employment and "getting £1 per week and found [lodgings and food]". When asked by the magistrate if he could contribute 15s per week, Albert said, "[H]e really could not. It came very hard on him; the children were all growing up and the eldest girl went to balls and all that sort of thing. He was sometimes not able to work at all and his wife would 'flash about'. "

This attempt by Albert to imply that Anastasia and Mary were living extravagantly was indignantly denied. Ananstasia claimed Albert had left her without food or a chair in the house and had told her to apply to the Benevolent Society. "She would never have him back with her as long as she lived. It was a pity some punishment could not be inflicted on her husband".

The magistrate finally ordered that 12s 6d per week be payed. Albert thanked the Court and promised to do his best. At the end of the court hearing, the reporter noted that "husband and wife walk[ed] out as perfect strangers" 21.

It seems as though Albert also walked out of the lives of his children. However the details are unclear; family tradition tells that he enlisted for overseas service in the Boer War and his daughter, Catherine used to sing about him going to the war.22 However, there is no Albert or Alfred Potter listed as serving in the New Zealand forces in the Boer War.23 There is no other evidence that he fought in the war and it is highly unlikely that he did. It may be that Anastasia told this story to hide her shame at being abandoned or it was a convenient explanation to her children for their father's absence. There is also another family story regarding the father of Mary which may also have been spread by Anastasia in order to cover the shame she felt about Mary's illegitimate birth. This story relates that Mary's father was a man named Ryan who died on the voyage out to New Zealand, a more acceptable story than the real one that she was seduced and then abandoned by Philip Fissenden. In fact there was a Thomas Ryan on the Caroline with Anastasia. Since he was single and from Tipperary, they no doubt became friends. However we know he survived the voyage, since no adult deaths were reported, and Anastasia's statements in court make it clear he wasn't Mary's father.

As far as we know Albert Potter did not return to Masterton and had no further contact with his wife or children. Other than the story that he remarried in Auckland, nothing further is known about him.

Anastasia continued living in Masterton bringing up her young family, no doubt still dependant on charitable aid, at least until the children were old enough to work. The photograph on the right, with her grandson Vincent (Mary's son), shows the house she lived in for many years. Family memories desribe her as a woman who remained both staunchly Irish and staunchly Catholic. As she grew older, she became less capable of looking after herself and her grandchildren would be assigned the task of going to her house and spending time with her.24

Eventually, in August 1926 when she was 72 years old, Anastasia was admitted to Porirua Mental Hospital suffering from senile dementia. She remained there for the next four years, but in late 1930 her health deteriorated and she died on 5th December, aged 76. Her daughter Mary was with her at the hospital25. She was buried in Masterton cemetery on the 7th December.26

References:

- Information supplied by Colleen Dale

- Anastasia Talbot's death certificate

- Thomas Talbot

- A short history of the Vogel Era

- The story was related to Colleen Dale by the Talbot family

- Marborough Express November 29, 1876

- Phillip and James Fissenden are listed in the Hannibal's passenger list.

- NZ Internal Affairs BDM, Record no: 1877/7252.

- Marborough Express December 5, 1877

- Marborough Express May 1, 1878. Philip Fissenden married Elizabeth Taylor in Blenheim in 1880. He died in 1918. It is not known if he had any further contact with his daughter.

- Talbot-Potter Wedding Certificate

- See the story of the Potter family here

- NZ Internal Affairs BDM, Record no: 1879/6163.

- Marborough Express August 30, 1880

- John:NZ Internal Affairs BDM, Record no: 1881/7632.

James:NZ Internal Affairs BDM, Record no: 1883/11318.

Anastasia birth:NZ Internal Affairs BDM, Record no: 1885/6590.

Anastasia death:NZ Internal Affairs BDM, Record no: 1885/2382.

Catherine:NZ Internal Affairs BDM, Record no: 1886/15771.- Related by Ben Summers (son of William, husband of Patricia Cross) to Denis Cross

- Wairarapa Daily Times July 15, 1892

- Wairarapa Daily Times December 16, 1892

- Wairarapa Daily Times March 21, 1896

- Wairarapa Daily Times May 1st, 1896

- Wairarapa Daily Times August 21, 1896

- As remembered by Patricia Summers (nee Cross

- In fact there is an Albert James Potter (serial number 8863) listed in the NZ Archives Gateway index. However, this is a mistake and the name should be Potier, not Potter. This mistake is also repeated in the Auckland Museum Cenotaph database.

- Meagan Holland (nee Cross) recalls her father Paddy saying he was sometimes given the task of caring for her.

- Coroner's Report

- Masterton Cemetery records show her as Annie Potter, buried in the old Archer Street cemetery, Plot AP, Row 7, Area Plan III. However, this plot is bare with no remains of a grave or headstone.