Ernest Percival (Percy) Fabien

BORN: Cedar Hill Estate, Trinidad. 26 June, 1919.

DIED: Killed in action, Kirkenes, Norway. 30 July, 1941.

Early years

Percy was the youngest of three children (at least until his sister Monica was born eight years later) in a family that was among the Trinidad elite. Little is known of his early life; all we have are some glimpses left to us by Monica and a few family photos that have survived. It was probably a privileged life. Percy's father, Ernest was manager of the Cedar Hill sugar plantation, supplying sugar cane to the factory in nearby Saint Madelaine. Monica describes their house as a wooden structure, with huge rooms and a very wide hall. There was a living room, a dining room and kitchen running along the front of the house. The rooms had large windows and looked out onto wide verandas. The house was set in large gardens with horse stables, a cricket ground and a tennis court. There were servants, including a cook and cleaner, and other sugar planters were frequent visitors. Percy grew up with his older sister, Marily and brother, John. Photo 1 shows them together in about 1923, with a little friend who is holding a tennis racquet and ball. We can imagine Percy's mother, Irene holding the camera that took this shot.

Their time together lasted for only a few more years; in 1925 Marily was sent, at the age of 10, to Cresent House School for girls in Bedford, England, while the boys remained in Trinidad. In December 1927, Monica was born, but the joy of another child was shortlived, since her mother seems to have suffered from depression and anxiety, although the exact nature of her mental illness is unknown. In a "Memorandum" written by Brian Bakewell (the husband of Irene's younger sister Hilda) he states that, "In 1928 shortly after Monica's birth, Mrs. Fabien had a nervous breakdown and came back to England; the next year she became worse and had to be certified in Aug. 1929"1 She remained in hospital for the rest of her life, until her death in 1982.

Irene sailed on the SS Bayano for England in October 1928, leaving behind John, Percy and Monica.2 She made her way to Bedford where Marily was at school and where her father, Dr John Gravely lived, and stayed with him to recuperate.

School in England

The following year the rest of the family followed her to England, in order to start the two boys at Wycliffe College in Stonehouse, Gloucester, for the beginning of the new academic year in September. There were no ships sailing directly from Trinidad to England, so Ernest, John, Percy and Monica first sailed to Demerara in Guyana (on the South American mainland) and boarded the S.S. Ingoma there.3 They docked in London on July 7th 1929 and then made their way up to Bedford.4

Irene would have welcomed the chance to see her children again. Far from being a joyous reunion, however, it seems as though Irene's state of mind worsened and in August she was committed to a mental institution.5

The boys started their new school and seem to have done well. According to Brian Bakewell, both boys were very strong and healthy, and good at games, especially John. In his opinion, "They [were] hard working but not brilliant." 6 They spent the occassional holiday with their Aunt Hilda and Brian at Hemel Hemstead and probably visited their grandfather in Bedford, but seem not to have returned to Trinidad.

Then in May 1932, Ernest Fabien died suddenly, probably of a heart attack. His death was a tragedy for the family. With their mother hospitalised and unable to take an active part in their lives, the four children were effectively orphaned. The expense of keeping Irene in hospital, plus the espenses of maintaining three children in boarding schools had put a considerable strain on the finances of the family. By the time of Ernest's death there seems to have been little left over. Marily had been forced to leave school in May 1931 and began work as a pupil teacher and help in an infant's school. The two boys were spared a similar fate due to their school's generosity in reducing fees. In addition, Ernest's employer, the Saint Madelaine Sugar Company gave the boys a grant although, while generous, was insufficient to cover the boys' school fees up to the normal age of leaving.

John left school and went into the Navy in January, 1934, but Percy stayed on at Wycliffe College until July 1936 when the last of the grant from the Saint Madelaine Sugar Company was finished. He was then 17.

Joining the Airforce

Percy's first choice of career was the Airforce, but unfortunately he failed the examination for appointment as an aircraft apprentice. On the advice of Brian Bakewell, instead of going into the Airforce without an apprenticeship, he found employment in an engineering works in Bedford, with the view to gaining experience. When the manager found Percy wished to learn engineering, he arranged an introduction with the aircraft engineering company, Philips & Powis Aircraft at Woodley Aerodrome, near Reading in Berkshire. They agreed to take Percy on as a "paid boy" but to move him around as an apprentice.

In the nearly three years Percy was with Philips & Powis he had worked in almost every section. He also studied mechanical drawing in his spare time with the aim of obtaining a position as a draughtsman. He also hoped to study for an engineering degree.

During 1939 it became increasingly likely there would be another war between Great Britain and Germany. In respnse to this the Military Training Act was passed in May, 1939 requiring all men aged 20 to 21 to register for military training. The Admiralty formed the Royal Naval Special Reserve (R.N.S.R.) in order to recruit men from this pool. Volunteers for the R.N.S.R. would therefore become subject to calling out by the Royal Navy rather than the army. As a 20 year old, Percy was required to register in one of the services. Consistent with his old ambition of joining the Air Force, he applied to join the Air Branch of the R.N.S.R. and was accepted. When war with Germany was declared on 3rd September, Percy joined the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) and began training in October.

Percy entered training as a TAG, a Telegraphist/Air Gunner. This may not have been his first choice and he may have preferred to enter as a pilot. However, there was no shortage of volunteers for the pilot branch, and at least one recruit was told at the recruiting office that he could join as a TAG and transfer to pilot later on. Once training commenced it was revealed that this was completely untrue, and a TAG he was to remain.7

Percy began his initial five-week training at the naval air station, HMS Royal Arthur near the holiday town of Skegness in Lincolshire. This was one of several assessment camps where new recruits were assessed, kitted out and sent to their various depots. Training involved naval general training such as drill, physical training and various medical and dental inspections, and was carried out alongside ratings training for other branches of the Royal Navy. After a week's leave Percy was transferred to the Royal Naval Barracks, HMS Victory in Portsmouth for basic training with other TAGs. Photo 4 shows Percy with other trainees at HMS Victory barracks in 1940. Thereafter, Percy and the other trainee TAGs moved to various naval shore bases around the country for further specialist training: a two-month signalling course, including wireless theory and Morse code, followed by flying training, gunnery, aircraft recognition, and maintenance and repair of machine guns. Photo 6 is taken in Winchester when Percy was at the training school (named HMS Kestral) for Telegraphist/Air Gunners in nearby Worthy Down. As the TAGs progressed, the exercises extended to cross-country flights. Once they had received their wings they awaited drafting to a frontline squadron. Percy received his during 1940 and in September was transferred to 827 Squadron.8

827 Squadron

827 Squadron was formed in September 1940 as a torpedo/spotter/reconnaissance squadron based at Yeovilton9 in Somerset.

The squadron was equipped with twelve of the new Fairey Albacore torpedo/bomber/reconnaissance aircraft which had entered into service in early 1940. The Albacore (see Photos 8 - 11) was a 3-seat biplane with a fully-enclosed cockpit for a pilot, observer and a gunner who doubled as the radio operator. The cockpit was divided in two by the fuel tank, so that the pilot in front had limited communication with the observer and TAG in the rear (see Photo 9). The Albacore also carried a torpedo under the fuselage, or bombs under the wings and had a top speed of 161 miles per hour (259km/h).10 Throughout the war the Albacores were flown mainly on coastal patrol, spotter-reconnaissance, minelaying and night-bombing duties. In 1941 they went to sea in HMS Formidable and other carriers and from then were active on convoy protection duties in the Baltic and in anti-submarine and other roles in the Mediterranean and elsewhere.

At first the squadron struggled with a lack of equipment and trained personnel. The new Albacores were not fully operational, missing aerials and bomb racks and with untuned radios. The somewhat chaotic situation provided Percy, along with the other new TAGs from Worthy Down, an ideal training opportunity.

By December, 1940 the squadron was fully operational and moved to the naval air station at Crail (HMS Jackdaw), on the east coast of Scotland in the Firth of Forth, to continue the next stages of training. They took off from Yeovilton in stinking, winter weather and landed in Crail in a sea of mud. Crail was even more chaotic than Yeovilton had been. There were no windows or doors on the huts they were to sleep in, and they spent their first night in oil skins. After much hard work, workshops were set up and proper accomodation was found for crews and mechanics. They then began their training: bombing, torpedo dropping, air firing and navigating, and the squadron started to build up into a highly functional unit.

Despite the unpromising start, the squadron considered Crail a very nice station. People were friendly and kind, and the crews enjoyed the evenings spent at the local pubs.

By spring 1941, they were ready to move to their aircraft carrier, HMS Victorious. The ship, however, was nowhere near operations standards so the squadron commanding officer, Commander Stokes volunteered the squadron to be attached to the RAF rather than have the crews doing nothing. Between March and May 1941, therefore, the squadron operated out of the RAF base in Stornaway on the Isle of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. From here they escorted convoys sailing to northern Russia and across the Atlantic, and carried out anti-submarine patrols. The whole squadron was billeted in the castle which dominates Stornaway.

In May the squadron moved south again to the RAF base at Thorney Island, east of Portsmouth, where it had the role of guarding against German warships using the English Channel, and conducting sorties to the French coast while looking for invasion barges. After only a week, the squadron was again transfered, this time to RAF St Eval, on the north Cornwall coast. It was a move they would all remember, because on the night of their arrival (5th May, 1941), St Eval was subject to a whole night of heavy bombing by the German Luftwaffe.

Percy talks about his reaction to the bombing in one of his letters to "Uncle Brian and Aunty", written from St Eval (dated 24th May, 1941).

I had my worst blitz the night we arrived. It blasted all night and only finished in the early morning. It really shook me up for days.The squadron was lucky in that the Germans had concentrated their bombing onto the buildings and administration areas of the airport, and had entirely missed the Albacores sitting out in the open.

Following this unpleasant experience, the squadron settled down to a routine of mine-laying operations off the French coast, near Cherbourg and Brest. The TAGs moved into the Bedruthian Steps Hotel, found out where the nearest pubs were and joined in the mid-week dance in nearby Newquay.

In the same letter, Percy also talks about some of the highlights of his busy year.

I had a good trip after my leave, from Donibristle to Stornaway in a "Fleet Air Arm Flying-boat & land-plane" (and amphibian). I made my first water landing at a sea-plane base on the west coast of Scotland where we stopped for dinner.And on his return:

I left Stornaway three weeks ago. We were at Thorney Island for one week before coming here. We flew all the way which helped my flying hours to date.But his letter ends on a more sober note.

Since coming to the south I have made a few trips over the invasion ports. I watch for night fighters with great interest.

Although we are standing by the whole day sometimes we do get opportunities to enjoy our surroundings. There is a good sand beach. I have had one bathe so far which was exceedingly chilly. We collected a bucket of mussels & cockles the other day. Perhaps they are an acquired taste for it was the first time I knowingly tasted them, and they tasted terrible, in spite of lots of vinegar...

If I am taken prisoner of war, or missing, or killed, you will have a letter from our C.O. of the sqdn. addressed to my Mother. Of course you will have to reply to this explaining my mother is ill and saying that you will pass the message to her. I thought you had better know the procedure but there is no need for anxiety. P.F.

Percy was on leave in London at the end of June. He wrote another letter to Uncle Brian & Aunty, dated 22nd June, saying he would be away from England for some time.

In all probability this will be my last letter written to you from England for some while. For the last week we have all been getting our aircraft and equipment ready for moving. We have also drawn our tropical kit and in a few days will be aboard our ship. That is the idea at any rate, but there is always the chance of altering everything. Personally I am all for moving now...

Far from heading for the tropics, however, the squadron returned to the far north, first stoppimg at Donibristle airfield to fit the new Identification Friend or Foe (IFF) equipment that would ensure they could be correctly identified as friendly aircraft. At the beginning of July they were at Royal Naval Station Hatston in the Orkney Islands where they undertook more training while they waited for their ship HMS Victorious. There was a feeling among the crews that something big was on. Finally, HMS Victorious arrived, and they embarked aboard the aircraft carrier along with 828 Squadron with their Fairey Albacores and 809 Squadron with Fairey Fulmar fighters.11

The big thing turned out to be "Operation EF", the code name for strikes on Kirkenes and Petsamo harbours. The plan was for surprise air attacks from two aircraft carriers, HMS Victorious and HMS Furious on Kirkenes and Petsamo respectively on 30 July, 1941.

Kirkenes and Petsamo

Kirkenes is located in the extreme northeastern part of Norway near the Russian—Norwegian border, about 400 km north of the Arctic Circle. Petsamo (it's old Finnish name), some 50 km further east, was once part of Finland but became part of the USSR after the short war between the USSR and Finland during the winter of 1939-40 ("the Winter War"). Petsamo and the surrounding area (also known as Petsamo) was re-taken by Finland with the help of its German allies in 1941, but lost again in 1944. Since then it has remained part of Russia, with the Russian name of Petschenga (see Map 12).

The surprise German attack on the Soviet Union, known as Operation Barbarossa, began on 22 June 1941. While the main attacks occured in the south, there were also attacks by Finnish and German troops in the far north in an attempt to capture the vital port of Murmansk.

The northern operation, known as "Operation Silver Fox", began with German divisions moving eastwards from Kirkenes and joining up with Finnish troops surrounding Petsamo. The port of Petsamo fell quickly from the shock of the surprise attack. The second phase was launched on 29 June, 1941 as German and Finnish troops marched across the barren northern terrain towards Murmansk. Exposed German vehicles in this coverless terrain became easy targets for Russian air and artillery attacks, and logistics became so difficult that the attack virtually halted as they approached the city. By September, the attack on Murmansk had failed and the Germans had to be content with bombing the port and the rail line from the port to the south.

The failure of the Germans to capture Murmansk had a profound impact on the outcome of the war, since it was one of the few ports open to the Allies for re-supplying Russia after its catastrophic defeats during the early weeks of Operation Barbarossa. Without this vital supply route, Russia could very well have been defeated in the early days of the war.

It was the strategic importance of Murmansk for the Allies, as well as Winstone Churchill's determination to demonstrate practical support for his new found ally, Stalin, that formed the background to plans to disrupt the supply lines of the German and Finnish troops attacking Murmansk. It was known that "Operation Silver Fox" was being supplied through the two northern ports of Kirkenes and Petsamo, and that Kirkenes was the headquarters of the German forces in the north. It was presumed that these two harbours would be full of shipping supporting the German war effort and so a strike here would cause the greatest disruption.

The raid

Although there was almost 24 hours daylight at this latitude at this time of year, it was hoped that the Fleet would remain undetected from enemy aircraft as they approached the Norwegian coast, and for most of the voyage low clouds kept it hidden from enemy aircraft. Unfortunately, about midday on the day of the raid the clouds thinned and finally cleared away with good visibility, and shortly before launch the Fleet was sighted by a German HE-111 reconnaissance seaplane. Despite having lost the crucial element of surprise, the decision was made to continue with the attacks.

Just after 2.30 pm HMS Furious dispatched its two Albacore squadrons (812 Squadron, followed by 817) with Fulmars from 801 Squadron, for the strike on Petsamo. The strike force then flew to the entrance of the Gulf of Petsamo towards the anchorages. In the event, the harbour was virtually empty. All the attackers could claim was the sinking of a small steamer and the destruction of several jetties for the cost of one Albacore and two Fulmars.

The strike on Kirkenes was a disaster, with the Luftwaffe prepared and waiting. The attack involved HMS Victorious dispatching twelve Albacores from Percy's 827 Squadron, eight Albacores from 828 Squadron, and nine Fulmars from 809 Squadron in two sub-flights. By the time the squadrons had flown down the fjord within striking distance of Kirkenes, the German defences had been fully alerted, with the Luftwaffe's Messerschmitt ME-109s and ME-110s already in the air. The squadrons claimed one 2,000 ton steamer sunk, another set afire, and minor damage ashore, as well as claiming two ME-109s and one ME-110 destroyed. However, losses were severe, totalling eleven Albacores and two Fulmars with eight other Albacores being damaged.12 Only six of the twelve planes from 827 Squadron returned to HMS Victorious, one of which was Percy's. Sadly, however, he was found dead in his cockpit.

Details of the attack were published after the war in the Supplement to the London Gazette. This document gives us some more detail of what happened to 827 Squadron and to Percy.

827 Squadron, on making a landfall at Rabachi peninsula, formed sub-flights astern, proceeded at low altitude down Jarfjord [a narrow fjord running parallel to Bokfjord where Kirkenes was situated], climbed the intervening hills, and then attacked shipping in Bokfjord.

Five aircraft attacked the BREMSE and two hits were reported. The remaining aircraft fired at shipping anchored N.E. and N.W. of Prestoy [a small island off Kirkenes harbour]. Torpedoes were observed running correctly towards two targets but owing to heavy fighter opposition encountered at this time it was impossible to observe the results. During the retirement heavy fighter opposition continued and one JU-87 was shot down for certain by a front gun, and a probable ME-109 with a rear gun. Six Albacores were lost. The air gunner [Percy] for whom the probable ME-109 is claimed, died in the aircraft and was buried at sea after the aircraft had returned to the ship.

A different, unofficial perspective comes from an extraordinary interview with Adrian Ernest "Dickie" Sweet, one of the other TAGs in 827 Squadron, who also took part in the strike on Kirkenes and was a witness to his death. Click here for a transcript of this interview.

The strike force of 827 and 828 Squadrons flew off HMS Victorious at 2.00 pm. A half a hour later the fighter escort of Fulmars from 809 Squadron took off to provide cover for the Albacores. 827 Squadron was divided into two flights with both Adrian Sweet in Albacore 4K, and Percy in 4L, following in the second flight. Once clear of the ship, they climbed to 500 feet and approached the coast. A hospital ship was anchored at the entrance to Kirkenes harbour. Any remaining hope of a surprise attack was now dashed, since the ship would certainly be informing the Germans of the Squadron's position. As 828 Squadron entered the harbour German machine-gunners were firing down on them from above. Percy's 827 Squadron proceeded more eastwards and flew up another fjord (Jarfjord) running parallel to Kirkenes harbour. At the end of this fjord they had to fly up and over the hill before dropping down into Kirkenes harbour. As they did so people from a farmhouse waved to them. Adrian Sweet spotted an Panzer-type armoured vehicle and let off a burst of machine-gun fire with little effect.

As they flew towards Kirkenes harbour the first thing that surprised them was the lack of shipping. They had been led to expect a full harbour, but all Adrian Sweet could see was a single merchant ship. Nonetheless, Sweet's pilot located a target and descended to torpedo-dropping height. The torpedo was dropped and the Albacore shot upwards with the sudden loss of weight. The pilot turned the plane as it was being shot at by a machine-gun post set in the hills above the town, and escaped into the fjord they had flown up.

Once in Jarfjord again they headed back towards the entrance. Up ahead they could see the Albacores from the first flight of 827 Squadron being picked off by German fighters. Adrian Sweet recalls the dread he felt at the sight:

As we approached the entrance to that fjord...high in the sky was one terrible, I remember to this day, a terrible circle of airplanes circling as they were picking off our aircraft as they ventured out of the fjord. So A, B, and C and F, G and H took the full brunt of exiting from that area...

The second flight of 827 Squadron did their best to evade the fighters as they made their way back down the fjord. Adrian Sweet's pilot hugged the sides of the fjord and on one occassion narrowly evaded a pursuing ME-109 by flying through a cleavage between two rocks. Following Sweet's plane was 4M, which was shot down, and Percy's airplane. In the 20 minutes or so they were in the fjord, they were constantly under attack. However Sweet's pilot managed to shoot down a Junkers-87 and Percy probably shot down a ME-109. Unfortunately, Percy's pilot was unable to evade another pursuing ME-109 and they received a burst of machine-gun fire from astern and under the aircraft. The burst decapitated Percy as it passed upwards and buried itself in the wings where they attached to the body of the plane, as well as shooting off the liferaft and damaging one of the wheels. The pilot managed to nurse the airplane back to the ship but when they landed on deck the two wings immediately fell off; all that had been keeping them on was the uplift on the wings. The airplane was lowered into a hangar below deck and Percy's body removed.

We can also glean further details of the attack, and Percy's role in it, from the letters of condolence sent to Percy's mother after his death. The two other crew of Percy's Albacore, pilot Richard Park and observer Oswald Hutchinson, believed that Percy had saved their lives. Oswald Hutchinson wrote:

I was in the back cockpit at the time of the unhappy incident, and I am very proud to be able to say that my air-gunner put up a most gallant show against overwhelming odds.

At the time we were making a torpedo attack on German ships in harbour. We came up against a very large number of German fighters which attack us time and time again, and right up until your son's death he returned shot for shot and almost certainly shot down one fighter.

Both the pilot and myself are quite confident that if Percy hadn't but up such a magnificent show we would never have survived the attack, and we have only got him to thank that we are still alive.

Herbert Ranald, Commander (Flying) aboard HMS Victorious, wrote:

The pilot of the aircraft, Sub. Lieut. Park, reported to me on landing. He told me that Fabien "fought like a tiger" with his one machine gun in the back cockpit, and that it was almost certain he shot down a Messerschmitt 109 which was last seen diving down over a hill with black smoke pouring from it. They were constantly attacked by two or three ME-109s at once over a period of 20 minutes. As you probably know your son's job was to work the wireless and fire the rear gun in an Albacore Torpedo-Bomber. In this case they were carrying a torpedo which they dropped at a ship off Kirkenes. An aircraft of this sort naturally is not designed to stand up to a fast 380 mph single seater fighter like the ME-109, and I don't know how they survived, especially against two or three. The aircraft was hit several times and one of the wheels was shot, the pilot having to land on the deck with a burst tire, which he did successfully. Both the pilot and the observer, who was alongside your son, escaped injury by a miracle. Your son was killed instantly by a bullet and cannot have suffered any pain of any sort, which is perhaps some consolation...

No Grave But the Sea

Percy was buried about 250 miles north of North Cape, the most northerly point of Norway and also of Europe, during the short night of the Arctic summer.13 The service was taken by the Reverend Dixon who described the scene in a letter to Percy's mother:

He was buried at sea from the Quarter Deck in the presence of the officers and men, among them his own friends.

It was late in the evening and everything was so quiet and peaceful. As I laid him to rest our prayers and thoughts were with you and others who were near and dear to him.

He was a brave lad and a son to be proud of. May he rest in peace!

After his burial, his clothes were auctioned off, according to naval custom. Herbert Ranald's letter continues:

He had only a small kit, just the necessary uniform, which would have fetched possibly £5 ashore. The sale realised £43.14.6, which has been or will be sent to you by the Naval Authorities. This will make you realise how much he was liked by the people who knew him. Sailors as you know are not rich, but they wanted to pay a last tribute of loyalty and show their admiration for a gallant shipmate the only way they could...

This good opinion of Percy is confirmed in a letter written by Herbert (Jackie) Lambert, another TAG in 827 Squadron. Lambert's letter is more than a letter of condolence; its tone suggests a lament for a dead friend. He writes of Percy:

Mrs Fabien, you have lost a son & I a grand chum but both of us can feel proud of the knowledge that we knew a great hearted brave gentleman who died, as he lived, with a willing smile, truly a hero.He writes of the hours before the Squadron took off for Kirkenes:

The last two hours, before taking off for the operation, were spent together by the Air Gunners of my squadron & no-one's laughter was more happy & carefree than Percy's — I tell you this because I wanted to confirm your own judgement that, great hearted and brave, he never faltered. He came to my machine just a few minutes before we took off, gave me that grand smile of his, shook hands & said, "Good luck, Jackie" and added our own pet phrase, "We'll show 'em". God knows he did and wherever he is resting now, I know that smile is still on his face, the smile of victory & a job well done. The memory of those last few minutes will always live with me & if I ever falter or feel afraid, they shall be my inspiration.

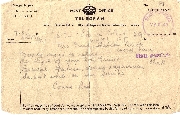

Uncle Brian and Aunt Hilda received the official telegram announcing Percy's death on the 7th August at their house in Hemel Hempstead and passed on the sad news to his mother, as he had instructed (see Photo 15).

Deeply regret to report

the death of your son Ernest

Percival Fabien, acting Ldg airman

Sr.648 while on war service.

"For gallantry, determination and outstanding devotion to duty in an attack on German shipping and harbour works at Kirkenes and Petsamo", Percy was awarded a Mention in Dispatches, as was Oswald Hutchinson. His pilot, Richard Park was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, and his friend, Jackie Lambert was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. A number of others from 827 Squadron were also given awards, as were men from the other squadrons. The list of awards was published in The London Gazette of the 17th October, 1941.

Percy's name is among the nearly 2000 names carved on the Fleet Air Arm memorial at Lee-on-Solent near Portsmouth (see Photo 16). The central column bears the inscription:

THESE OFFICERS AND MEN OF THE FLEET AIR ARM DIED IN THE SERVICE OF THEIR COUNTRY AND HAVE NO GRAVE BUT THE SEA 1939-1945

References:

- Brian Bakewell. Memorandum on the Children of Mrs. E. E. Fabien. 24 July, 1939.

We don't know what the purpose of this Memorandum was, but the title and the formal language suggests a legal purpose.- Passenger list for S.S. Bayano

- Passenger list for S.S. Ingoma

- The Gravely address was 58 Bushmead Avenue, Bedford.

- Brian Bakewell. Memorandum...

- The information on Percy's early life, up until his joining the R.N.S.R., has been provided by Brian Bakewell in his Memorandum...

- Barber, Mark. The British Fleet Air Arm in World War II. Osprey Publishing, 2008. p.13

- Barber, Mark. op.cit. pp.13-14.

- See Wikipedia for a history of RNAS Yeovilton

Yeovilton is also the site of the Fleet Air Arm Museum. See the museum web site here.- See Wikipedia for more information on the Fairy Albacore

- Information on the movements of 827 Squadron between September 1940 and July 1941 is from an interview with Adrian Ernest "Dickie" Sweet, who also served as a TAG with the squadron. The audio recording of the interview is held by The Imperial War Museum, Catalogue Number: 18624. For further details go to the catalogue page here

See also the 827 Squadron dairy held by The National Archives, Reference: ADM 207/26. For further details go to the catalogue page here

There is a brief mention of 827 Squadron in the Fleet Air Arm Archive site here.- These details are from the Fleet Air Arm Archive 1939-1945 site.

- These details are from letters of condolence written to Percy's mother. For example we know Percy was buried at night because the Rev. Dixon relates how he was unable to get a photograph of the burial because it was too dark. At these latitudes, at the end of July, there is about an hour and a half of night (or twilight).

- From the collection of James Richard Steele. See other photos from this collection here

- Note the Observer's seat behind the TAG's position. Also the large red petrol tank separating the Observer and Pilot. This photo is from Pier Francesco Grizi's model site here.

- Barber, Mark. op.cit. pp.20.

827 Squadron was based in Crail on the Firth of Forth at this time. Note the marking 4M (centre); the numeral 4 identifies this as 827 Squadron, followed by individual aircraft letters. Percy was flying in 4L during the attack on Kirkenes.- This photo is from the Imperial War Museum Collection.

- This photo is from the Naval History site: Russian Convoys 1941-45.

- This photo is from the Imperial War Museum Collection.

Sub Lieutenant G Dunworth is being carried from his Fairey Albacore on the deck of HMS Victorious after being wounded by gunfire during an attack on the German battleship Tirpitz off the coast of Norway.