Francis Lot (Paddy) Cross

BORN: Masterton, 13 June, 1896

DIED: Wellington, 2 April, 1968

Early Years:

Paddy was born in Masterton, the youngest of ten children, and christened Francis Lot. The name Lot was given in honour of his father's uncle Lot Cross who farmed at Cross' Creek near Featherston until his death in 1891. It is not known where the name Francis came from since there seem to be no relatives with that name. At some time in his life, however, he was given the name Paddy and since this is the name his family best knows him by, Paddy will be used in this biography. However, he did sign himself Frank Cross on his army papers and he was probably known as Frank during the years of his army service.

As in many large families, there was a wide spread of ages between oldest and youngest, and his oldest brother Charles was 20 years older. His father, Daniel left New Zealand in about 1900 and never returned to New Zealand, and prior to his leaving, Daniel seems to have spent very little time at home, so Paddy would have grown up with very few memories of his father. We can assume that his older brothers became his surrogate fathers.

This section to be continued...

War Service 1916-1919:

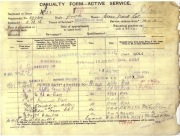

The following account of Paddy's war service is mostly taken from his army personnel records, held by Archives New Zealand in Wellington1. One of these forms is the Casualty Form-Active Service (Army Form B108), detailing Paddy's record of transfers, promotions and casualties (See Photo 2). Unfortunately, none of Paddy's letters home seem to have survived and, as far as we know, he didn't keep a dairy. Nor did he speak much about his war experiences when he returned home. So we have no direct knowledge of his experiences during these years, and we have to rely on the recollections of others to fill in the gaps, to get an impression of what his experiences may have been like.

Before enlisting, Paddy lived with his mother at Homebush, just outside of Masterton, and this is where he returned to after being discharged from the army in 1919. Before enlisting he was employed as a driver by S. Foreman.

Enlisting

When the war with Germany broke out in 1914, men in their thousands flocked to enlist. By 1916, however, the seemingly endless toll in lives and maimed men began to impact on public sentiment. Intensive campaigns to encourage enlistment failed to meet their targets, with only 30 percent of men eligible for military service volunteering. In order to maintain New Zealand's supply of reinforcements, conscription was introduced with the Military Service Act 1916 that required all men of eligible age (20 to 45 years of age) to enrol in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force by 16th September.

Paddy enlisted soon after, on 2nd October 1916, for the "Duration of War". He may not have been conscripted, since many men, faced with eventual conscription anyway, often decided to volunteer. His brother Arthur had enlisted five months earlier and this would have influenced his decision. Paddy had already tried to enlist but had been rejected as unfit due to varicocele, a usually harmless swelling of the veins of the scrotum. Clearly, faced with a shortage of men, the army chose to ignore this minor condition. He was otherwise fit and healthy, 5 feet 7 1/2 inches (171.5cm) tall, which was slightly below the average of 5 feet 8 inches (172.7cm) for New Zealand soldiers in World War 144, and weighed 161 lbs (73kg). Colour of hair medium dark; eyes blue; complexion fair; religious profession, Ch. of England.

Training

Having said goodbye to his mother and family, Paddy began began military life at Trentham Camp on 14th November, along with hundreds of other new recruits. On their first day, the men were paraded for medical inspection and received an inoculation against typhoid. They were required to take an oath of allegiance and drew their first lot of kit. They were then allotted their numbers and platoons. Paddy became Pte. F. L. Cross, Regimental No. 39767, assigned to J Company, 23rd NZ Reinforcements.

Jesse Stayte (19th Reinforcements), from Auckland, describes the sense of bemusement felt by the new recruits:

Discarded all civilian dress and commenced drill in real earnest and I am afraid some of us must have just looked what we were, a lot of Duds and instead of drill I think we wandered about like a lot of sheep.

However our Officers are lenient and after a while we began to get on better and get our minds on our work, then we forged ahead although I fear very slowly at first.2

They spent a good deal of their time drilling and going on route marches. Rifle exercises began when they were given their rifle and bayonets. On Sundays, they had to fall in for Health Inspection and Church Parade. Once they had their uniforms, groups were permitted leave in Wellington. Jesse continues:

Some of the Boys are on leave every evening and a lot of them return drunk and make a noise and sometimes there is no sleep to be got until 2 or 3 in the morning...Got leave today, Saturday, and spent the Evening in Wellington and the mob was very rowdy going home in the train and quite a number of windows were broken.3

After about three weeks at Trentham, they moved to the camp at Tauherenikau, just north of Featherston, where they received their second typhoid innoculation. The recruits didn't like Tauherenikau at all. It was very exposed to the winds off the mountains and was bitterly cold in winter. They lived in tents which were far from waterproof and their clothes and bedding were often damp. Thankfully they didn't spend long there, and soon moved to Featherston Camp where they completed their training.

Featherston camp was opened in January 1916 to accommodate increasing numbers of recruits to the army and became New Zealand's largest military training camp during World War One. The camp also became the biggest settlement in the Wairarapa, housing up to 8000 men at any one time, at different stages of training. The training period at Featherston was from two to four months, depending on the type of soldier. They learned to march, dig trenches, fire their rifles, machine guns and artillery cannon, manage horses, obey orders quickly, and to live together in large groups. 4

Ira Robinson, from Lyttleton, was in the same group of recruits as Paddy. He describes the training to his father:

We were shifted back to Featherston Camp last Saturday week from Tauherenikau and I was very pleased , I can assure you, as I did not like the place at all. However, we are here now and having a real good time of it, even if we are drilling a bit harder than previously. We are now getting into the advanced stages of our training, such as bayonet fighting, outpost & scouting work and entrenching, also night marches, etc, so you can see we are getting on. It is all very interesting and when one goes through it all one begins to realise to what a fine pitch the art of fighting has come. The different stages of the attack under artillery fire are very complicated to explain on paper, but if I come down I will show you just how it is all done...5

A great novelty was the wearing of shorts by the men. Ira Robinson wrote to his father:

There is one thing that helps us a great deal [when we are doing drill] and that is we wear very little clothes, only a shirt, a short pair of pants, puttees and boots. The short pants, shorts they are called, are just all right as they keep your legs nice and cool.6

Another diaryist, Lawrence Chambers (29th Reinforcements), insisted on writing "shorts" in quotation marks.

The change in lifestyle, unfamiliar discipline, as well as being away from home and loved ones, must have been difficult for many of the men. The short periods of leave given to the soldiers made life bearable. Paddy, as a Wairarapa soldier, was a short train ride from family and friends and the temptation to delay the return to camp just a little longer must have been too great at times, since in January, 1917 Paddy was arrested in Masterton for overstaying his leave. For this he was fined two day's pay and confined to barracks for three days. About two months later, when he was in Trentham camp, he again overstayed his leave (this was probably his "final leave" taken just prior to embarkation), this time being fined one day's pay.

At the end of training in Featherston the 2094 men of the 23rd Reinforcements were marched over the Rimutaka road back to Trentham camp. It was quite an occasion whenever a group of reinforcements marched off. Jesse Stayte describes the sending off of the 19th Reinfrcements:

Up at 5.30am and got all our gear packed and carried over to the transport waggons and had breakfast and put on our packs (full), got our Rifles and lined up ready to start off on our march to Trentham, and moved off at 8am...

We marched through Featherston Camp where the band picked us up and played us to the foot of the Range and left us. When we were halfway up the range it commenced to rain and by the time we reached the summit we were wet through.

At the summit we were met by a large party of Ladies from Masterton and they provided us an excellent luncheon and hot tea, for which we were very thankful. Considering what a beastly day it has been I think these Ladies deserve far more thanks than they ever get and I am sure I shall always think much of their kindness.

The Little Shoemaker from Featherston is at the Head of our Column with his flag. He always marches over the Range at the Head of every Reinforcement.

We had one hour for lunch and then pushed on, cheered on by the Ladies who so kindly provided us with our Lunch. We reached Kaitoki at 4.30 wet through, having marched 17 miles through the rain. We had to bivouac anywhere we could and the only way we could get a dry place was to dig all the wet soil away and lay down with an oilsheet over us...We had a rum ration and that kept us warm and we passed a fairly good night.7

After another night in the open, they wearily marched into Trentham, then spent the next week readying themselves for the voyage to England.

Departure for England

The first group had departed for England on the troop ship Ruapehu on the 14th March 1917. The second group, including Paddy, sailed on Tuesday 3rd April on the Corinthic8, no doubt waved goodbye by his mother and well-wishers. Photograph 9 (right) captures the occasion.

Again we rely on Jesse Stayte, to give us an idea of what it was like for the soldiers and their families as the ships departed:

This has been one of the most momentous days of my life...

Had lunch and dressed for our last Public Parade in Dear Old New Zealand. I got a Wire from my Mother and Sisters. Looking anxiously for one from my Home but got none. I think it must have been sent to another Troopship.

We lined up and started our Parade through Wellington at 2pm. The Streets were crowded with cheering people and they continually threw flowers amongst us and everyone was trying to shake hands with us as we passed and all were wishing us luck. The march was grand but it was very sad, the ranks full of Fathers, Mothers, Sisters, Brothers and Sweethearts and at times we could hardly keep our formation. I felt very glad that none of my Family were there although I felt very lonely just then and would have shaken hands with a dog.

At the Wharf Gates all Civilians were kept back until the Soldiers got aboard, which we did about 4pm and then all friends and relatives were admitted. The Wharves were crowded in a minute and hundreds of tapes of different colours were thrown out between Soldiers and Friends and a half hour spent in a last conversation (alas the last for ever for many) and I felt so lonely in all the turmoil I yearned for some one to speak to.

As our ship began to move out at 5pm the excitement was extreme and pitiful and I shall never forget that scene as we left the wharves, for Parents and Sweethearts and other Relatives were either crying or cheering.

We pulled out into the Harbour about a mile and dropped anchor and got our tea, although I do not think there were many who cared for tea that night. We hung about the decks until 10pm when our last mail came aboard and I got 2 letters from Home and as there was no sign of sailing we went to bed after taking a last look at the Town.

At midnight we were awakened by the throb of the Engines and we knew that we were leaving old New Zealand and all we held so dear.9

The Corinthic departed Wellington unescorted since the German navy had been eliminated for the Pacific and Indian Oceans by the end of 1914. After weeks out of sight of land they arrived in Cape Town on 3rd May. The men were granted shore leave and spent the days touring around Cape Town. They ate out at local cafes (Joe's Cafe did a good hot meal for 1/-) or at the Troops Entertainment Rooms1-. The Corinthic departed Cape Town on the 10th May in a convoy of 8 boats, including other troopships. As they neared the African and European continents, all ships and convoys maintained a zig-zag pattern to lessen the risk of being torpedoed or their courses being accurately plotted by active German U-Boats. Four hundred miles out from England ten destroyers picked up the convoy, escorting them through the dangerous waters to Plymouth11. The men were required to wear life jackets and took turns on submarine lookout duties. They finally anchored in Plymouth Harbour on the 10th June 1917.

Training in England and France

After disembarking they were transported by train to Sling Camp, the largest and best known camp of the New Zealand camps. Sling Camp was situated in the heart of the Salisbury Plains near the village of Bulford and just a short distance from Amesbury and Stonehenge. Reinforcement troops were subjected to a hard regime of drill, marching, bayonet fighting, shooting, grenade throwing, trench and gas warfare training and lectures on the latest tactics. The camp seemed to be universally disliked; the discipline could be brutal for the slow, the incompetent and those who tried to buck the system, and the weather on the exposed Salisbury Plains could be bitter. Once he was in camp, Paddy was posted to C Company, 5th Reserve Battalion, New Zealand Rifle Brigade with the rank of Rifleman.

The New Zealand Rifle Brigade, was formed on 1 May 1915 as the 3rd Brigade of the New Zealand Division, and so is also referred to as the 3rd New Zealand Rifle Brigade (The 4th Brigade was established in March, 1917, under the command of Brigadier-General Herbert Hart, Paddy's mother's cousin.). The Brigade was made up of four battalions, referred to as the 1st Rifles, 2nd Rifles, etc. The Official History of the New Zealand Rifle Brigade, written by Lieut.-Col. W. S. Austin and published after the war in 1924, is the most complete recounting of the Brigade's fortunes, from its formation until it was disbanded in February 1919.12

On the 6th July, after a month at Sling Camp, Paddy left for France, probably landing at Boulogne. On the 10th, Paddy and his unit were marched into Etaples Base Camp where they spent the next month completing training.

Today, Etaples is a fishing town about 27 kilometres south of Boulogne. During the war, the area around Etaples was the scene of immense concentrations of Commonwealth reinforcement camps and hospitals. It was remote from attack, except from aircraft, and accessible by railway from both the northern or the southern battlefields. In 1917, 100,000 troops were camped among the sand dunes and the hospitals, which included eleven general, one stationary, four Red Cross hospitals and a convalescent depot, could deal with 22,000 wounded or sick. The camp was notorious for the harshness of the discipline. Under atrocious conditions both raw recruits from England and battle-weary veterans were subjected to intensive training in gas warfare, bayonet drill, and long sessions of marching at the double across the dunes. After two weeks at Etaples many of the wounded were only too glad to return to the front with unhealed wounds. Conditions in the hospital were punitive rather than therapeutic and there had been incidents at the hospital between military police and patients. In September, just three weeks after Paddy had left the camp, tensions came to a head after the arrest of a New Zealand soldier. The gathering of a large group of angry men sympathetic to the arrested man's situation soon developed into one of the largest mutinies of the war amongst British troops.13 While Paddy was not directly involved in this incident, he would have experienced the building up of tensions and heard about the incident.

At the Front

On the 12th August 1917, Paddy finally arrived at the front and was posted to A Company, 2nd Battalion, New Zealand Rifle Brigade. This group of men were to be his family for the next year. Unfortunately for Paddy however, August, September and October were to prove the worst months of the New Zealanders' campaign in France.

The general objective of the British Army in the Northern Sector of France had been to eliminate the "bulge", or salient, around the town of Ypres and to secure the high country to the east, which overlooked Ypres, in order to improve their defensive position (see Map 19). To this end, the New Zealanders had particpated in the successful capture of the village of Messines (to the south of Ypres) on the 7th June14. When Paddy joined his new battalion, the Rifle Brigade was still in the line just south of Messines, and experiencing the wettest August in memory.

Wet weather was a disaster for the soldiers on both sides because much of the Ypres area is below sea level; the land consists of a thin crust of soil concealing reclaimed swampland. With the constant churning of the soil and the disruption of normal drainage by almost two years' of constant shelling, the land had reverted to swamp. The flooded trenches and sodden landscape of this battlefield are among the most potent symbols of the First World War.

Apart from the Germans, the New Zealanders' biggest enemy was the mud. Soldiers often had to wade through foul-smelling viscous mush at the bottom of the trenches and finding a dry spot to rest or sleep was often impossible. Trenches often collapsed on sleeping men as the soil became more sodden, or when a trench was hit by shell-fire. Many troops succumbed to trench foot, a fungal infection caused by immersion in cold water. Rats and lice were soldiers' constant companions: rats, having gorged on corpses, allegedly grew 'as big as cats'; lice were the (then unknown) vector of another common wartime ailment, trench fever. Stinking mud mingled with rotting corpses, lingering gas, open latrines, wet clothes and unwashed bodies to produce an overpowering stench. The main latrines were located behind the lines, but front-line soldiers had to dig small waste pits in their own trenches. The application of chloride and lime to protect against disease and infection only added to the stink.

At night the trenches often became hives of activity. Despite the continued risk of night bombardment or trench raids, the cover of darkness allowed troops to attend to vital supply and maintenance tasks. Rations and water were brought to the front line, and fresh units swapped places with troops returning to the rear for rest and recuperation. Construction parties beavered away repairing trenches and fortifications, laying duckboards and wire and preparing artillery positions. An hour before daybreak, everyone would stand to in readiness for action as another day dawned over the bleak battlefield.15 The sights, smell and noise of the front line must have been overwhelming for newcomers like Paddy.

The official history of the Rifle Brigade relates these difficult times:

The weather was wet and cold and the conditions generally were worse than [previously experienced]. Owing to the excessive shelling, especially on the left battalion area, which was on the forward slope of Messines Ridge [that is, facing the Germans], the communication-saps had been completely destroyed. The front-line trenches were for the most part thigh-deep in mud, devoid of duck-boards, and quite without shelter beyond the shallow little "cubbyholes" which had been excavated in the sides and which possessed no other value than that they enabled those men who were not immediately on duty, and were endeavouring to snatch a little sleep, to get their legs out of the slimy mess.16

A huge effort went into repairing the trenches and carrying out patrols, despite the appalling weather and "unusually intense artillery and aerial activity". They were finally relieved by the Australians on the night of 22nd/23rd, no doubt to Paddy's great relief. By the end of their exhausting tour in the trenches 26% of the Rifle Brigade had reported sick.

Paddy's record shows no more entries until the following year when he was granted leave in September 1918. He was in the field, therefore, for almost thirteen months continuously, which seems an considerable feat of endurance and luck, especially since he also participated in the disastrous attack on Passchendaele on the 12th of October.

After being relieved from the trenches at the end of August, the Rifle Brigade spent an arduous September burying cable and road-making around Ypres. These duties entailed long marches over difficult shell-hole country with most of the work done at night, sometimes in gas-masks under shell-fire. Casualties continued to mount, with 200 casualties sustained by the Brigade over September. The weather, at first fair, became bitterly cold, and as the men had neither blankets nor warm underclothing, they had little sleep.17

The battle for Passchendaele

After two months of slogging in often appalling weather, the British Army had taken most of the high ground overlooking Ypres. However, the ridges leading to the village of Passchendaele remained firmly in German hands. The first step in taking Passchendaele was the Battle of Broodseinde on the 4th October. This was a stunning success and, at the time, was considered one of the greatest victories of the war. The New Zealand Division captured all its objectives, advancing the British line by nearly 2,000 yards and taking 1,159 German prisoners, but at a cost 1,853 casualties.18

The next step was to be the final assault on Passchedaele itself but wet weather intervened again and turned the battlefield into a quagmire of thick, glutinous mud. Three months of shelling had destroyed the natural drainage of the region and the thousands of shell holes now filled with muddy water. When the attack began on the 12th October, exhausted s oldiers struggled through thick mud, with inadequate artillery cover and against uncut wire into well protected German conditions. Nothing at all went to plan and, as a result, New Zealand suffered not only a severe military defeat but its greatest ever human catastrophe. Not a single objective was taken and the cost was massive. Some 846 New Zealanders were killed on this one morning and a further 2,000 soldiers were wounded. Another 138 New Zealanders died of their wounds over the next week. More New Zealanders were killed or maimed in these few short hours than on any other day in the nation's history.19

Ira Robinson, who was in the same battalion as Paddy, describes the difficulties the Rifle Brigade had just to get to the starting line:

We started at about 5pm, just as it was getting dark, and quietly left our camp near Ypres. Each man was well loaded up with rifle, bayonet and ammunition, equipment, steel helmet, two bombs, shovel, six sandbags, one rifle, grenade, oil sheet, overcoat and two days' rations and a full water bottle, also a pair of socks, knife, fork and spoon and two gas helmets, which altogether I can assure you weigh a good deal, about 60 pounds or more. Well, we set out and our troubles began. With this load up we started to walk along about 4 miles of duckboards, as we call them; at least we were on the boards sometimes, at others we were in the mud alongside where we had slipped off into mud up to our knees. It was awful, I can tell you, and old Fritz shelled us all the way... After walking about four hours in the dark and rain - it now started to rain - we were halted and told to make ourselves as comfortable as we could, which meant we were to dig in and try and get a little sleep if we could. Our section...dug in and were not so bad for a while in spite of the wet and old Fritz's shells, which were falling thick and fast all round and among us. Then the water started to come in the trench and a little later the sides of the trench fell in and we had to dig it out again. Altogether we dug it out three times that night, and in between we bailed the water out with a bully beef tin. You can imagine the amount of sleep we got, as it was very cold and rained all the time.

Ira Robinson describes the horror of the failed attack:

Just as the dawn was breaking our barrage opened up and we got the long-looked-for word to advance. We hopped over...and from then on it was just one horrible nightmare. There were the boys getting killed all round us, some of them getting the most terrible wounds. It was awful. Our Company went in with 146 men and came out with 40, the rest were either killed or wounded. However, one has no time to notice much and we advanced in spite of old Fritz and we captured his front line of trenches and several machine guns, also a good many prisoners. All the time our boys were getting fewer and fewer. After we got the first line I never saw my mates again, and only after we came out did I find out they were wounded. We kept on going for about 800 yds, where we were held up by two pillboxes which our artillery had failed to smash. There we had to dig in under old Fritz's rifle and artillery fire, which was no bon, and we lost an awful lot of the boys before we got properly dug in.

Now comes what I reckon was the worst feature of the whole affair. All the stretcher-bearers were killed or wounded and the wounded had to just lie where they were, in some cases for 24 hours on end. It was awful to hear their groans all through that awful day and night. We could not help them as we had to hold the line and there were only a few of us left by now. Our officer and all the NCOs except one in our platoon were either killed or wounded and we were in a bad way, there were so few of us...

All that day we held on and the night, also the next day, until the following night when we were relieved after putting in five days and nights in mud up to our knees and without anything to eat or drink except our 24-hours' rations, which we carried with us when going in, and what we could collect from dead men lying round. However, we got out safely. what was left of us, and a sorry looking lot we were. Some without coats, others without puttees, and most with their clothes all in rags and tatters, and all dead hungry and weary and just tottering with fatigue. The saddest part of all was calling the roll the next day. Since we came out we have been resting, as most of us have very bad feet now and we require a rest badly...20

Paddy was one of the lucky ones and escaped the disaster without being wounded. However, his brother Arthur, serving with the Otago Regiment, was badly wounded with gunshot wounds to the shoulder, no doubt a victim of the devastating machine gun fire that took so many lives.

Assisted by clearing weather, the Canadians eventually captured Passchedaele and by the 10th November 1917 they held the whole of the ridge. However, when the Germans launched their great spring offensive in April of the following year it became impossible to hold the ridge, and Passchendaele was given up. The area held by the British Army shrunk to comprise little more than the ruins of Ypres and the immediate outskirts, so that in April 1918, after some 275,000 Allied casualties, the situation returned to as it was a year earlier.

Morale in the New Zealand Division after its attack on 12th October plumeted. The men were exhausted and sickness was rife. Letters to loved ones back home show that, for the survivors, the war seemed never-ending and ceased to have a purpose. We can assume that Paddy shared in the general depression.

The Rifle Brigade, along with the rest of the New Zealand Division, spent the 1917/18 winter in the area to the east of Ypres. Generally speaking, the Brigade had a tour of about a week in the line, followed by a similar period in support, and then went out to reserve for the same length of time. The New Zealand Division settled in repairing and extending trenches, patroling, and training new recruits. Heavy snow-storms commenced on December 3rd and continued through December, making movement difficult and increasing the discomfort of the men. In early January came rain and a thaw set in which turned the ground everywhere into an oozy mess of mud. Many of the trenches collapsed and soon became knee-deep in mud. Even though this was a "quiet" sector, the New Zealanders were constantly harrassed by shelling and sniper fire and the Brigade continued to suffer about 200 casualties a month.21 However, with better weather, conditions improved, as did the men's fitness and spirit. Then on 21 March 1918, news came of the enemy push in front of Amiens, to the south of Ypres.

Stemming the German offensive

By November 1917, Russian resistance in the east had entirely ceased and the Germans, instead of having to conduct a war on two fronts, were now able to concentrate all their forces in Belgium and France. The Germans planned a great spring offensive in order to take best advantage of of these reinforcements before the arrival of US troops. The plan was to sever the connection between the British Army in the north and the French in the south, and capture the vitally important railway city of Amiens.

When it became evident that the Germans were trying to exploit a weakness in the Allied defences to the north-east of Amiens, the New Zealand Division was ordered to entrain to the south and to plug the gap against the rapidly advancing Germans. As New Zealand battalions, exhausted after forced marches and nights out on the road, began to arrive in the early hours of the 26th March, they were organised into makeshift "brigades" and pushed forward to engage the enemy. They were confronted by streams of fleeing refugees and retreating British soldiers. Later in the morning of 27 March the New Zealand artillery began to arrive and by evening most batteries were in position. The guns went into action without delay on arrival. The gap had been closed in the nick of time. Maps 25 and 26 show the area held by the New Zealand Division.

The New Zealand sector of the front was under almost constant attack in the days following. Despite cold weather, lack of adequate clothing, food and water, the New Zealand Division not only consolidated its position, but on the 30th March was able to launch a significant attack on the Germans, so that by the 31st, they were in a fairly positive position on the high ground overlooking a faltering German advance.

Morale was generally high, especially since the battle was beginning to swing in favour of the New Zelanders. However, by April 1918, Paddy had been fighting almost continuously for eight months, often in the most difficult conditions. The following dairy entry hints at the exhaustion suffered by many of the soldiers at this satge of the war:

Still in the trenches. I am tired, sore and heart broken of this Hellish life. Just one continual roar of the guns and shell and bullets flying all around everywhere...I have not had my clothes off for 2 months or more now, no blankets now only Great coats and as lousy as coocoo [sic]. God knows when it will come to an end this Hellish life.22

Even in periods when the troops were out of the line, much time was taken up in training, inspections and working parties: making roads, digging trenches, all heavy physical work, so that men become physically worn out by two or three years of heavy, unremitting toil. Away from the front line the soldiers continued to be subjected to enemy shelling and air attack.

Reinforcements who joined the Division in the middle of this operation also found the experience hard. Paddy's brother Percy joined the 2nd Battalion of the Auckland Regiment on the 5th of April, on the day that the Germans made a last desperate effort to break through to Amiens. The day started with the heaviest and most sustained artillery bombardment the New Zealand Division experienced during the war. Despite the intensity casualties were surprisingly light, but the experience must have been terrifing for the inexperienced Percy. The rest of the day was spent dealing with infantry attacks which died away in the afternoon, effectively bringing the German offensive in that area to a halt.23

On the 23rd of April Percy was evacuated sick with an acute ear infection, but rejoined his unit on the 9th of May. Then on the 19th of May Arthur rejoined his unit, so that for the first time in the war, all three brothers were in the field together. Since the fighting had died down, there is no doubt the three of them would have taken the opportunity to spend time in each other's company.

Then on the 18th of July, Arthur was killed. We have almost no information on the details of his death. His service record states only that he was "killed in action in the field", and the history of the Otago Regiment provides no clues. Paddy related later that the three brothers were together and going forward when they were attacked. Paddy said they all headed for a pond of water nearby; Percy and Paddy made it but Arthur didn't and they never saw him again.24 However, there are some problems with this description of his death. The first is that the three brothers, being in different regiments, were not fighting together. Arthur's Otago Regiment had moved into the front line the previous day and was positioned at the north of the New Zealand line, around Rossignol Wood (see Map 26)25. The Rifle Brigade was relieved from the front line on the same day and moved back in reserve to Chateau de la Haie, where they remained for the next eight days26. Percy's Auckland Regiment was also in reserve, near the village of Sailly27. Since the Germans were constantly shelling the New Zealand lines, he may have killed by shell fire. Or he may have been killed in one of the many small-scale raids undertaken by the New Zealanders as they continued to push forward against the German positions. We will probably never know how he died, but his record states he was buried by the Rev. David Herron in the Gommecourt Chateau cemetery. Since Paddy and Percy were both in reserve, it is highly probable that they were able to attend their brother's funeral.

Photo 33 shows the Rev. Herron conducting a military funeral at a newly dug grave at Gommecourt, with the burial party of soldiers looking on. A total of 8 burials took place here on this day, Friday 26th July, 1918. This is probably not a photograph of Arthur's funeral, since the information we have on the photo states that the men being buried are from the 2nd Otago Battalion, whereas Arthur belonged to the 1st. In addition, these burials occured eight days after Arthur's death and it is unlikely that he would have remained unburied for that length of time. However, it is most likely that he was buried in this same place, by this minister, attended by these men, or men like these that Arthur knew. He was later reburied in the Gommecourt New Wood cemetery, where he lies today.28 We will never know the exact details of his death and burial, and can only imagine the feelings of his brothers at this time, but this photo brings us as close to these events as we can possibly get.

During the night of 2/3 August, Paddy and his 2nd Rifles battalion relieved Arthur's 1st Otago battalion in the line to the east of Rossignol Wood. The enemy artillery bombardment of the area, and especially of Rossignol Wood, continued steadily day by day, frequently rising to great intensity, and this was supplemented by trench mortar activity on the front trenches. Whenever possible, raids were carried out into the German trenches in order to gather information on their positions and to capture prisoners for interrogation. On the evening of August 10th Paddy's battalion was relieved in the line, going back to reserve in their old quarters in the Chateau de la Haie. There they spent a brief but enjoyable period of rest. The weather now was fine and warm, and the calls for working-parties being less exacting than usual, recreational and general training went on with little interruption.29

The great spring offensive was the closest the Germans came to victory on the Western Front. It was the darkest time for the Allies and shook the military establishment to its core. For the first time they had faced the real possibility of loosing the war. However, while the Germans had spectacular early successes, by July it was clear that the offensive had petered out and they had been thrown back onto the defensive. Along with other units of the Allied armies, the New Zealand Division continued to advance at every opportunity and by the 16th August occupied the western part of Puisieux, pushing the Germans back some three miles since the end of March. The Germans' failure had cost them the initiative, as well as almost a million of their best soldiers, the very backbone of the force. The effect on morale is revealed in the dairy of a German officer killed in Rossignol Wood a few days after Arthur's death there:

We have lost our best men and what we have left are such that we cannot rely on them. It makes a man sick to see the good men sinking fast...The men are done to death.30

This was not to imply that the German Army was incapable of further fighting. While full-scale offensive operations were probably out of the questions, the army was still capable of conducting stubborn defensive operations, which the New Zealand Division found to its cost when it took the town of Bapaume between 21st August and 2nd September. This battle saw some of the toughest, and costliest, fighting of the war for the New Zealanders. Claude Wysocki, a corporal in Paddy's 2nd Rifles describes what came to be known as "Bloody Bapaume":

I was there. We went in there with a complete unit of 125 and we came out with less than 50; less than half that number. Bapaume - that was the bloodiest of the lot that one. Bapaume, oh yes that was dirty.31

On leave

Despite the heavy casualties, Paddy came through the fighting unwounded. Percy was unwounded as well, but sprained his ankle, and was evacuated sick on the 30th August. Then on 3rd September, Paddy was promoted to Lance Corporal. Probably even more welcome was the announcement that he had been put on the list for three weeks "Blighty" leave, his first since joining his battalion over twelve months earlier. He left his regiment three days later on the 6th.

We don't have any record of Paddy's time on leave, but we do have the dairies of other solders, which give us a good idea of what it was like to be a New Zealand soldier on leave at this time. In particular, is the dairy of Jesse Stayte who was given leave at the same time as Paddy. This is his dairy entry for the 3rd September, written in the matter-of- fact tone that characterises many of these dairies:

We are still in the trench and we were on working party digging trenches on what was last night No-Man's land. Our dead are lying very thick around here. I thought I knew the features of a man I saw lying dead and I took out his paybook to see who he was and I was sorry to see it was Harry Smith of Tuakau, a young man I had known well.

We shifted at 7pm and came forward abour 2 miles and dug in an old trench. Fritz is still falling back rapidly. Bombs were again dropped tonight. My name was taken today for Blighty leave so I expect to be away on leave in a day or so. Our Cooks came up today and we are now able to get some hot food for which we are thankful.32

Paddy, no doubt thankful to be away from the line after all this time, gathered with the other men on leave, about a thousand men from different branches of the army. Jesse Stayte describes how they were given new uniforms, passes and ration cards and made their way by train to Boulogne. The men stayed overnight at a rest camp and marched to the boats the next morning. As soon as they got to the wharf it started to rain very heavily and rained all the way over the Channel. After arriving at Folkstone they had a fast run by train to London and arrived at Victoria Station at 4pm. As soon as they left the train everybody was given tea and cake and free bus tickets to Russell Square, near to both the Y.M.C.A. and the Soldiers' Club.

London, the centre of the British Empire and famous for its buildings and history, was the place of choice for many on leave, helped by cheap, clean and safe accomodation. The New Zealand Y.M.C.A. had a large hostel in Bloomsbury where bed and breakfast was 2 shillings. The New Zealand Soldiers' Club in Russell Square, with 200 beds, provided much the same. New Zealand soldiers were enthusiastic tourists and family visitors. Men travelled far and wide over the British Isles to be with relatives, usually never met before. We have to wonder if Paddy met up with his father Daniel, or his Uncle Charles, or Aunt Lotty-Jane. The answer, sadly, is probably not since Daniel seems to have kept his New Zealand marriage and family a secret from his new wife and probably made no effort to stay in touch with his children. Paddy may have had no knowledge of his relatives in England.

After three weeks leave Paddy returned to his battalion on the 29th September. On the 1st October he was promoted to Corporal, in charge of one of the sections (a squad of some 7-15 privates) in "D" company, 2nd Battalion, New Zealand Rifle Brigade.

Assault on the Hindenburg Line - the last days

Paddy returned in time for the Allies' all out attack on the Hindenburg line. This was a system of fortifications including concrete bunkers and machine gun emplacements, heavy belts of barbed wire, tunnels for moving troops, deep trenches, dug-outs and command posts, and was considered impregnable by the Germans. Between the towns of Cambrai and St. Quentin, the Hindenburg Line took advantage of the canal system which ran through steep-sided cuttings. Despite the Hindenburg Line's fearsome reputation, the Germans were pushed out of their main defensive lines in a series of battles between the 27th of September and the 9th of October, with the capture of the St. Quentin Canal and Cambrai.

The objective of the New Zealand Division in this advance was to secure the St. Quentin Canal between the villages of Vaucelles and Crevecouer, about four miles to the south of Cambrai. By the 28th of September, the New Zealanders had successfully battled their way to the Canal at Crevecour, with units crossing into the town. Despite their continuing defeats, the German army continued to put up extraordinary resistance, right to the very end of the war, and none of the Allied victories was easy. For the New Zalanders, the casualties, already heavy, became increasingly severe.

The Rifle Brigade, which had been in reserve, went into the line during the night of 3rd/4th October. There had been very heavy shelling on Crevecoeur by the Germans during the morning of the 2nd, and again during the evening of the 3rd, while the relief was in progress; and on the following morning there were signs that the enemy was about to deliver a counter-attack against the village. The expected action did not follow, however, and patrols cautiously went out to check the position and strength of the German forces.33

On the 8th of October the New Zealand Division continued its advance in an effort to secure the high ground east of Crevecoeur. The attack began at 4.30 a.m. with artillery fire directed at the German positions. As the troops moved forward they met considerable resistance. A succession of sunken roads lying across the path of the New Zealanders held concealed enemy machine-gun posts that would open up on the troops as they passed. Great care had to be taken since they could be easily missed in the dim light of early morning. The advance was characterised by a succession of skirmishes as each machine-gun post was overcome. One such machine-gun post was threatening Frank's section. The Official History of the New Zealand Rifle Brigade describes the action:

...two of "D" Company's sections under the command of Corporal F. L. Cross and Rifleman W. A. Mackinder, respectively, met with considerable resistance and were held up by a machine-gun post. The two leaders, working in co-operation, handled the position skilfully. One held the front while the other took his men to a flank, and, closing in, they cleared the position with a dashing rush, taking twenty prisoners and two machineguns. 34

Paddy was awarded the Military Medal (See Photo 38) for this action. The entry in the London Gazette describes the reasons for the award:

Conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty during operations in front of Crevecoeur on 8th October 1918. Corporal Cross led his section round the flank of an enemy trench where two strong enemy machine gun posts were holding up the advance of his Platoon, and by good tactful handling and daring he cleared up the trench and captured the machine guns with 20 prisoners. Beside this a number of the enemy were killed by rifle fire and bombs by his section. Throughout the advance this NCO displayed great courage and initiative under heavy fire.35

At some time during the day, Paddy himself was a victim of machine gun fire, bringing to an end his extraordinary run of luck, as well his participation in the war. We have no details of the incident other than the cryptic entry on his Casualty Form that he was wounded with gun shot wounds to the right thigh and left arm, and evacuated to the casualty clearing station and then to the hospital at Camiers, near Etaples Camp. It seems as though Paddy may not have been very seriously wounded since he was transferred to a Convalescent Depot in Etaples a few days later on the 12th. Convalescent Depots were half way houses for casualties returning to the front - men who no longer required hospitalisation but were not yet fit to rejoin their units. A week later he was transferred to the Convalescent Depot at Ecault, south of Boulogne, and then discharged on the 23rd October. He returned to his unit on the 6th November to the congratulations, no doubt, of his comrades for his Military Medal.

Two days earlier, on the 4th November, the Rifle Brigade had dramatically captured the ancient town of Le Quesnoy by storming the town's ramparts. The Brigade spent the next day in the town as guests of the grateful citizens before going into reserve, while the rest of the New Zealand Division continued to fight their way eastwards, until they too were relieved on the 6th.

End of the war - Armistice

At an early hour on November 11th, a telegram, on the ordinary pink field-message form, was received from the Division headqarters, conveying the instruction: "Hostilities Cease at 11 A.M. To-Day." The conditions of the armistice were received and spread about the following morning. The great news was received with extraordinary calmness by all ranks; there was no excitement whatever, and training went on without interruption. After parade hours the terms of the armistice and the prospects of an early and certain peace were quietly discussed by little knots of men.36 It was as though nobody could quite believe what had happened.

Bert Stokes, from Wellington, a gunner with the New Zealand Field Artillery, recounted that momentous but strange day:

It seems too wonderful to believe. There is no cheering or excitement, just a feeling of relief. Everything is going on as before, we still have the horses and guns to look after, but of course we miss the screeching shells screaming over the enemy lines. We all have taken it in a calm and subdued manner. Nobody seemed to want to cheer when we first heard the news. We realised that soon we shall see the home shores on the horizon and that is what the armistice means to us. For most of us tired in body and mind and with memories of the tragic field of battle this momentous anouncement was too vast to be appreciated at that moment.37

Army of Occupation

Much to the men's dismay, the New Zealand Division was detailed to form part of the Army of Occupation across the Rhine. This news was met with widespread dissatisfaction. The men insisted that they had enlisted for the duration of the war and, now that it was over, they should be sent home as soon as possible. However, discipline was maintained and on November 28th the Division commenced the long march to Germany.38

By December 3rd, they had crossed the border from France into Belgium and before long they were in country that had escaped the fighting. The men were astonished to realise they had left behind the region of battered villages, ruined factories, broken bridges, and mined cross-roads, and were entering a different world. As they tramped through the towns, the people poured from everywhere and gave them overwhelming welcomes, cheering them on. During their short stops they were treated with remarkable kindness and hospitality, with families vying with one another to secure one or more of the men as private guests. 39

Once they had arrived at the German border, their march was at an end, and they entrained to Cologne. The Division marched into the city. "With quick and sprightly step, our men swung along with the proper air of conquerors, disdainful alike of the discomforts of the pouring rain and of the fact that the passage of their column was dislocating the city's excellently-conducted tramway system."40

The Division spent three months in Germany, settling down to an easy time of training and recreation. However, the main thing on most of the men's minds was demobilisation and returning home. The long process of disbanding the Division began, and those due for leave, as well as those evacuated sick, did not return to Germany. By the end of January drafts from the Division were leaving at the rate of 1,000 men per week. Despite orders that had forbidden fraternisation with the German population, it was noted that "when they left Cologne the [train] platform was a seething mass of weeping German maidens"41. Paddy's turn finally came on the 25th of February 1919, with orders to report to Sling Camp.

The return home

When Paddy re-entered Sling at the beginning of March he no doubt expected an early return to New Zealand. However, troop ships were not available much to the frustration of the men anxious to return home. It was decided they must be kept occupied and so the spit and polish regime that was a characteristic of their earlier training period was continued, along with route marches. The famous "Bulford Kiwi" was carved into the chalk hills above the camp in an effort to ease tensions, where it remains today. The men requested a relaxation of discipline but were refused. Infuriated at the refusal, they went on the rampage, looting the canteen and the officers' mess, drinking all the liquor and causing extensive damage. 42

William Kingston, from Dromore in Canterbury, who also served in the Rifle Brigade, lamented the loss of discipline that came with the disbanding of the units:

Codford [another camp close to Sling Camp] the last few weeks has been unbearable, discipline has gone to the pack and the troops don't care a damn for officers and NCOs. The big canteens are simply gambling dens. All sorts of games of chance are being conducted and no notice is taken of the orders that say it has to stop. As fast as boats are available, men are despatched but everybody is impatient and as there is no leave issued prior to a boat leaving many men just hire a taxi and decamp for a week...43

We don't know what role, if any, Paddy played in the riot. However, we can assume that the general frustration was affecting him as well, because on April 1st he left camp without leave for four days until he was apprehended on the 5th. For this he forfeited four days pay.

Then on the 14th April he was admitted to hospital with mumps and was not discharged until the 3rd of May. This may have been lucky timing for him, although he probably didn't think so at the time, since being in the hospital may have isolated him from an outbreak of Spanish flu that claimed many lives in Sling Camp, and in the other surrounding camps. Ironically, many of the victims, who had travelled 12,000 miles from home and survived the hell of trench warfare, ended up dying from the flu after the war was over.

His brother Percy remained in Etaples for most of this time until the 20th May, when he was moved to Codford. If they met, it would they would have had only a few days together, because on the 27th May, Paddy finally sailed for home. He left from London on the SS Tahiti. It had been almost two years and two months since he had sailed from Wellington. Poor Percy didn't leave England until November.

After the War:

This section to be continued...

References:

- Archives New Zealand Personnel Record Title: Frank Lot Cross. Archives Reference: AABK 18805 0030356. These records have recently been digitised and can now be viewed online at Personnel Record for Frank Lot Cross

- Miller, Ross. From Within the Ranks. The World War One Dairy of Private Jesse William Stayte. Ross Miller, 2003. p23.

- Miller. p25.

- Featherston Camp

- Ward, Chrissie (ed). Dear Lizzie. A Kiwi Soldier Writes form the Battlefields of World War One. HarperCollins, 2000. p13.

- Ward. p16.

- Miller. p30.

- Embarkation of Reinforcements from New Zealand 1914-1918

- Miller. p33.

- Frances, N. & King, D. Things have been pretty lively. The Great War Dairy of Melve King, Wairarapa Archive, 2008. Melville King was from Carterton, part of the 20th Reinforcements that left NZ in January 1917. His dairies are a fascinating account of his training in Featherston, the voyage to England and military service in France.

- Presbyterian Church Archives: New Zealand at War : 1914-1918 (Page One) This includes an interesting collection of photographs of the 23rd Reinforcements from the Moore Collection.

- Austin, Lieut.-Col. W. S. The Official History of the New Zealand Rifle Brigade. L. T. Watkins Ltd., Wellington, 1924.

This is also online at The Official History of the New Zealand Rifle Brigade- Wikipadia: Etaples Mutiny.

See also: Ellis, John. Eye-deep in Hell. Trench Warfare in World War I. Taylor & Francis, 1976. pp179-180.- See the The Ypres Salient website for a good overview of the 1917 campaign.

The New Zealand History Online: Passchendaele-fighting for Belgium site also gives an excellent overview of the campaign from a New Zealand perspective.- New Zealand History Online: Life in the trenches.

- Austin, p226-7.

- Austin, p230.

- Harper, Glyn. Massacre at Passchendaele. The New Zealand Story.HarperCollins, 2003. p42

- See Harper's Massacre at Passchendaele for a general coverage of the battle, and Austin's The Official History of the New Zealand Rifle Brigade for the NZRB's role.

- Ward. pp57-60.

- Austin, pp252-271.

- Harper, Glyn. Dark Journey. Three key New Zealand battles of the Western Front. HarperCollins, 2007. p280

- See Harper's Dark Journey for a general coverage of the battle

- As recalled by Shirley Hawthorn (nee Cross)

- Byrne, A. E. Official History of the Otago Regiment, N.Z.E.F. in the Great War 1914-1918. J. Wilkie & Company, 1921. p310.

This is also online at Official History of the Otago Regiment- Austin, p339.

- Burton, O. E. The Auckland Regiment. Whitcombe & Tombs Ltd., 1922. p225.

This is also online at The Auckland Regiment.- More details of Arthur's death, burial and burial site, with photographs, is given in Arthur's biography.

- Austin, pp340-1.

- Harper, Dark Journey, pp329-332.

- Harper, Dark Journey, p325.

- Miller, R. From Within the Ranks. The World War One Dairy of Jesse William Stayte. Ross Miller, 2004. p123.

- Austin, pp400-1.

- Austin, pp412.

- London Gazette, 14 May 1919, p6062, Rec. No. 3012.

Also quoted in McDonald, W., Honours and Awards to the New Zealand Expeditionary Force in the Great War 1914-1918. Helen McDonald, Napier (Pub), 2001. p74- Austin, pp436.

- Stokes, B. 1914-1918. The Years of World War One. Quoted in Pugsley, On the Fringes of Hell. p283.

- Pugsley, C. On the Fringes of Hell. New Zealanders and Military Discipline in the First World War. Hodder & Stoughton, 1991. p283-5

- Austin, pp473-76.

- Austin, p478.

- Pugsley, p292.

- Pugsley, p290.

- Wilson, W. K. Dairy, 1915-1919. Quoted in Pugsley, On the Fringes of Hell. p291-2.

- Inwood, K., Oxley, L. & Roberts, E. Rather above than under the common size? Stature and Living Standards in New Zealand. Paper for presentation to UCLA Von Gremp Workshop in Economic and Entrepreneurial History. 16 November 2009. Retrieved from http://www.econ.ucla.edu/workshops/papers/history/roberts_rather_above_than_under.pdf